That Australians do not spend their super in retirement, and supposedly have more super and other financial assets when they die than when they retired, has become a misleading and underlying theme in narratives about the strengths and weaknesses of the Australian superannuation system.

For instance, the recent Retirement Income Review Report stated :

“This [the findings of a number of studies] suggests that retirees tend to consume only the income derived from assets and not the assets themselves.”

Despite such claims being widely quoted, there is little or no evidence that the typical Australian dies with around the same amount of financial wealth as when they retired, other than cases where there was not much financial wealth in the first place. Sadly, the main group having the same amount of superannuation when they died as when they retired are those who retired with no superannuation.

Australian Taxation Office data on superannuation balances

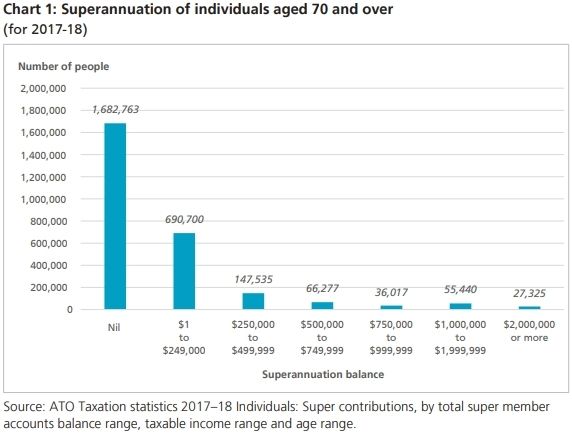

ATO data indicates that current superannuation balances for those aged 70 and over are, in most cases, quite modest (Chart 1 and Table 1).

The 1.02 million individuals with superannuation equate to around 37% of ABS estimates of the number of Australians aged 70 and over as at June 2018. Around 1.7 million Australians aged 70 and over have no superannuation at all.

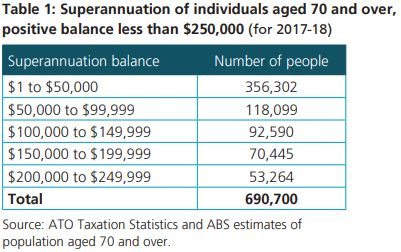

For the minority aged 70 and over with superannuation, the median balance falls within the $100,000 to $149,000 range. Only around 185,000 individuals had a superannuation balance of $500,000, with 27,325 individuals having more than $2 million in superannuation.

Around 14% of those aged 70 and over with superannuation continued to receive the benefit of employer contributions.

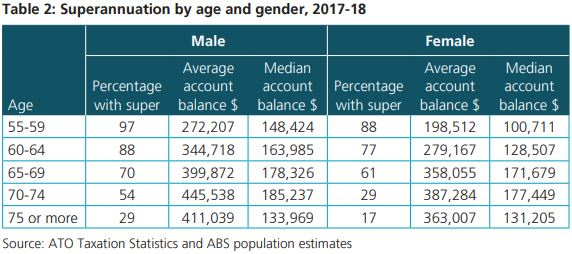

The ATO statistics also show a fall in the incidence of superannuation that increases with age, particularly for females (Table 2)

As at June 2018, 54% of males aged 70 to 74 had superannuation, while only 29% of males aged 75 or more had superannuation. For females, 29% of those aged 70 to 74 had superannuation, falling to 17% for those aged 75 plus.

In comparison, 97% of males and 88% of females aged 55 to 59 had superannuation.

Given that compulsory superannuation for employees has been in place since 1992 (with coverage rates around 40% before that), these falling rates of superannuation coverage mainly come from many individuals withdrawing all of their superannuation over the course of their retirement.

Only a very small proportion of people have substantial balances at any stage after age 70.

Evidence on superannuation balances shortly before death

ASFA also has investigated what sort of superannuation balances people have just prior to death.

Through making use of data from waves of the Australian longitudinal household survey, HILDA, it is possible to identify people who died and their age at death. It is also possible to track their last observed superannuation balances in a period of up to four years prior to death.

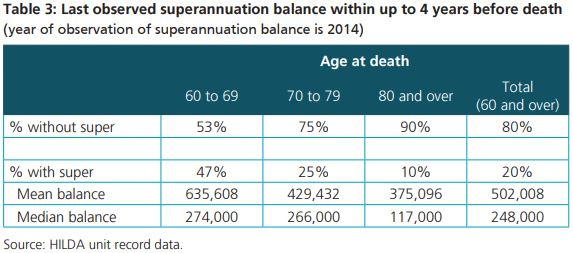

Table 3 shows the superannuation status of individuals in the HILDA survey sample who died at the age of 60 or older in the four years to 2018. Table 3 also shows the mean balances, the percentage of individuals with a positive superannuation, and for those with positive balances, the mean and median.

In the various tables the sample sizes for those who did have superannuation are of relatively small size. Accordingly, caution is needed in interpreting the mean and median figures for the relatively small proportion of those in the survey who still had superannuation prior to death. However, the pattern of these results makes sense with, for instance, declining proportions of those with superannuation in the older age groups examined.

The HILDA data in Table 3 shows that 80% of people aged 60 and over had no super at all in the period of up to four years before their death.

For the minority that still have superannuation, the amount can be substantial, with a mean balance of around $500,000 in 2014 for those who died in the four-year period to 2018. This figure is well up on the figures for 2010 and 2006 (see the Appendix to this paper), reflecting the maturing compulsory superannuation system and that some individuals have very high balances.

As shown by Table 3, those who were aged 60 to 69 at the time of their death were more likely to have superannuation than older age groups.

Many in this age group would still be working and/or would have been drawing down on their superannuation for only a limited period. This younger cohort also would have had the benefit of compulsory superannuation for longer periods than older age cohorts.

However, people who die in their 60s often have medical issues impacting on their ability to work and any superannuation available is often taken as a lump sum retirement benefit or TPD release prior to death.

For those aged 70 to 79 the incidence of superannuation starts to fall away with only around 25% still having superannuation in the period before death. Mean and median balances are also lower for those who still had superannuation.

For those aged 80 plus, the incidence of still having superannuation is quite low, with over 90% having no superannuation in the period of up to four years before death. However, a very small proportion still had superannuation, sometimes a substantial amount.

For the age 80 plus group, only 5% of that group had more than $110,000 in superannuation in the period of up to four years before their death. The average superannuation balance for the 10% of this age group that still had superannuation is around $375,000, reflecting the small number of retirees with high superannuation balances.

Men are more likely to have superannuation than women in the four years before death. For those who died in the period 2014 to 2018, only 15% of females aged 60 plus at death had any superannuation compared to around 25% of men.

The ages at which people die and APRA data on death benefits

There are far fewer superannuation death benefits paid than there are deaths in Australia. As well, a significant proportion of superannuation death benefits from funds relate to individuals who have not yet retired. Insurance benefits in regard to such individuals also boost death benefit payments. For these individuals, having a significant superannuation death benefit available is a strength rather than a weakness of the superannuation system given that in most instances there will be a spouse, infant orphan or other financial dependent.

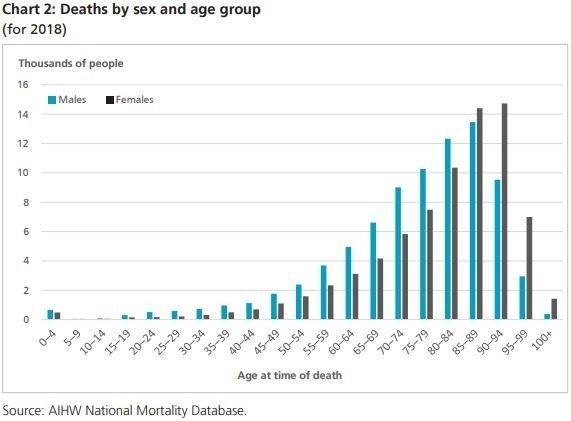

Most deaths in Australia occur after age 60, with around 87% of deaths occurring after that age (Chart 2).

Comparatively, in 2018 there were over 18,500 deaths of persons aged 20 to 59. The great bulk of this age group would have had a superannuation account or accounts, given the compulsory superannuation system and high levels of labour force participation of those in that age group.

APRA statistics indicate that in 2017-18 around 16,000 life insurance claims were paid. The great bulk of those would have related to those aged under 60 given that insurance cover generally ceases at age 65 and labour force participation begins to fall after age 60, leading to a cessation of insurance cover for those concerned.

APRA statistics indicate that in 2017-18 funds with five or more members paid out 40,000 superannuation death benefits and a further 9,000 benefits linked to a terminal medical condition. This compares to around 157,000 deaths of individuals aged 15 and over.

The average benefits were around $128,000 for death benefits and around $90,000 for terminal medical condition benefits. These averages are boosted by the 16,000 or so accounts which had average life insurance payouts of around $147,000.

After adjusting for deaths of the 18,500 individuals aged under 60 (the great bulk of which would have had a superannuation balance) and for multiple accounts, the APRA statistics are fully consistent with HILDA data with only 20% of those aged 60 and over having a superannuation account balance when they died.

The Retirement Income Review Report concluded that in 2019 one in five dollars of benefit payments from superannuation funds was for death benefits. The source of the data underlying that conclusion is not entirely clear. However, it is possible that it relates to the total death and terminal illness benefit payments as a proportion of total lump sum payments.

Calculations made by ASFA based on total benefit payments (including pension payments) and adjusting for death benefit payments (including life insurance payouts) for those who have not retired indicate that, for APRA regulated funds, in 2019 around one in eighteen dollars of total benefit payments were death benefits related to the superannuation of those who have retired.

While this ratio may fall to a degree in future, the calculation indicates that the superannuation system delivers benefits predominantly for retirement and related purposes.

Data on death benefits paid by self-managed superannuation funds (SMSFs) are not available.

Conclusion

The vast majority of people exhaust all of their superannuation well before their death, with a smaller proportion passing on some superannuation to their spouse and with a relatively small proportion undertaking estate planning which benefits other generations.

This is consistent with the lived experience of most people and their families.

As a result, here are a couple of policy implications:

- Given that a large proportion of current retirees have very modest superannuation balances, the case is strengthened for increasing the SG to 12% (as currently legislated) so that retirees can live in retirement with dignity.

- There is a small proportion of retirees who have superannuation balances greater than can be reasonably justified given the tax advantages provided to superannuation. ASFA recommends that individuals be required to withdraw any superannuation they have that is in excess of $5 million.

Ross Clare is Director Research and Resource Centre at The Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia Limited (ASFA). This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.